There is wide support for writing GUIs with Python with many different toolkits. These toolkits, binary modules for Python that interface with native code written in C/C++, all have different APIs and different feature sets. Only one comes with Python by default: the TK GUI toolkit.

Other options are wxPython, PyQT, and pyGTK. For this series of articles, we will be using Tkinter, which is Python’s standard GUI package and comes installed with Python. It is perhaps the most used GUI programming kit and is portable across virtually every platform.

Installing Tkinter

If you installed Python under Windows, the Python Windows installer includes Tcl/Tk as well as Tkinter. This is essentially a one-click install of everything needed. Linux and the BSD platforms require a separate installation of Tcl/Tk. This is usually available as a binary package. Under Ubuntu/Debian/Mint, you can use the following command:

sudo apt-get install python python-tk idle python-pmw python-imaging

This installs Python, Tkinter (which is not really needed since it automatically gets installed with Python), IDLE, Python MegaWidgets and PIL. In Fedora Core, it’s:

yum install tinker

Getting Started with Tkinter

The first thing to understand is that most GUI frameworks, including Tkinter, are based on a widget model. A widget is a component of a GUI. Buttons, labels and text boxes are all widgets. Most widgets have graphical representations on screen, but some widgets (such as tables and boxes) exist only to contain other widgets and arrange them on the screen. A GUI is constructed out of an arrangement of widgets.

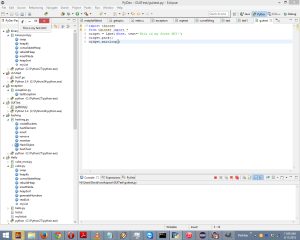

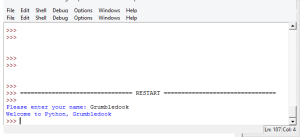

In this script, we create a GUI of a simple window and a label:

import tkinter from tkinter import * widget = Label(None, text='This is my first GUI') widget.pack() widget.mainloop()

The first thing the script does is import the Tkinter module. Next, we could either import Label from Tkinter, for simply import all (*) from Tkinter (we did the latter). After that, we create an object for each widget (in this case, Label). The Label is then arranged in the parent window. Finally, the widget is displayed.

This is acceptable as a first GUI script, but it would be nice if the label would re-center itself when the dialog box that contains it is resized (if you try to resize it, you will see that this is not the case). However, we can fix this with a small code change:

import tkinter from tkinter import * Label(text='This is my first GUI').pack(expand=YES, fill=BOTH) mainloop()

When you run the program, try resizing the window. You will see the “This is my first GUI” text label stay centered no matter what the window looks like.

In these initial examples, we created the widgets and configured them at the same time. However, we may want to wait to configure them after they are created:

import tkinter from tkinter import * root = Tk() widget = Label(root) widget.config(text='This is my first GUI') widget.pack(side=TOP, expand=YES, fill=BOTH) root.mainloop()

In this example, we called upon the configure method to achieve the same result as in the previous example. If we wanted to, we could change the appearance of the widget later in the program.

Recent Comments