Form and function are key to creating a good GUI. In this article, we’ll go one step further and control the actual appearance of widgets.

Up to this point, we have used the default look for our widgets. This is somewhat drab, so to create programs that are visually appealing, we want to tweak the look of our widgets. For example, we can change the font and background/foreground colors.

import tkinter

from tkinter import *

root = Tk()

labelfont = ('times', 36, 'italic')

widget = Label(root, text='This is a test.')

widget.config(bg='black', fg='blue')

widget.pack(expand=YES, fill=BOTH)

root.mainloop()

Although all the program does is display a window with some text in it, the design does draw the user’s attention.

Radio Buttons and Checkboxes

In addition to windows, frame, labels and buttons, sometimes you want to use radio buttons and checkboxes to give your users more choices. Aside from appearance, radio buttons and checkboxes differ in one significant way: radio buttons offer users a list of options, but allow them to select only one; checkboxes offer users many options and lets them choose as many as they want.

For example, here’s some code that implements radio buttons:

import tkinter

from tkinter import *

state = ''

buttons = []

def choose(i):

global state

state = i

for btn in buttons:

btn.deselect()

buttons[i].select()

root = Tk()

for i in range(4):

radio = Radiobutton(root, text=str(i), value=str(i), command=(lambda i=i: choose(i) )

radio.pack(side=BOTTOM)

buttons.append(radio)

root.mainloop()

print("You chose the following number: ",state)

This program creates a series of buttons ranging from 0-3 (four in total) with the number 1, 2 and 3 highlighted by default. The user can then choose any of the buttons. Once a button is chosen, any other button’s state becomes False, meaning that the button is no longer selected. When the users close out of the program, they are given a statement showing which number they chose.

For a similar effect with checkboxes, try this code:

from tkinter import * states = [] def check(i): states[i] = not states[i] root = Tk() for i in range(4): test = Checkbutton(root, text=str(i), command=(lambda i=i: check(i)) ) test.pack(side=TOP) states.append(0) root.mainloop() print(states)

The last line in the program is print(states), which prints out the states list – the values of the check boxes. This, if you check off boxes 1 and 4, your result will be:

[True, 0, 0, True]

Dialog Boxes

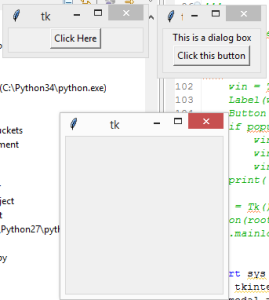

Sometimes you will want to give the user a piece of additional information. You have probably seen dialog boxes in programs. They pop up whenever there is an error, or a program wants to confirm something. Tkinter offers two types of dialog boxes: modal and nonmodal. Modal dialog boxes wait for some action from the user before going away, andpause the progress of the program. Nonmodal dialog boxes do not interrupt the flow of the program.

Creating a dialog box in Tkinter is almost a trivial process. For example, we can create a simple function to generate a dialog box like so:

def dialog(): win = Toplevel() Label(win, text='This is a dialog box').pack()

We need some means of invoking the dialog box from the main window, so the main program will have this code:

root = Tk() Button(root, text='Click This', command=dialog).pack() root.mainloop()

You will also need the usual headers at the beginning:

import sys from tkinter import *

This will create a main window, and when you click on the button in the main window, it will launch a simple, nonmodal dialog box that has some text in it. This is OK, but we really want a dialog box that actually does something, so let’s rewrite the dialog function:

def dialog(): win = Toplevel() Label(win, text='This is a dialog box').pack() Button(win, text='Click this button', command=win.destroy).pack() if makemodal: win.focus_set() win.grab_set() win.wait_window()

You will need to add this line before the dialog function:

makemodal = (len(sys.argv) > 1)

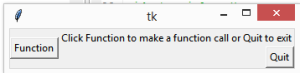

When the button in the main window is clicked, the program will launch a modal dialog box and that box will take the focus. When you click on the button in the dialog box, it will close itself, and the original window will take back focus.

Recent Comments